Young Adult Cancer and Becoming a Death Doula

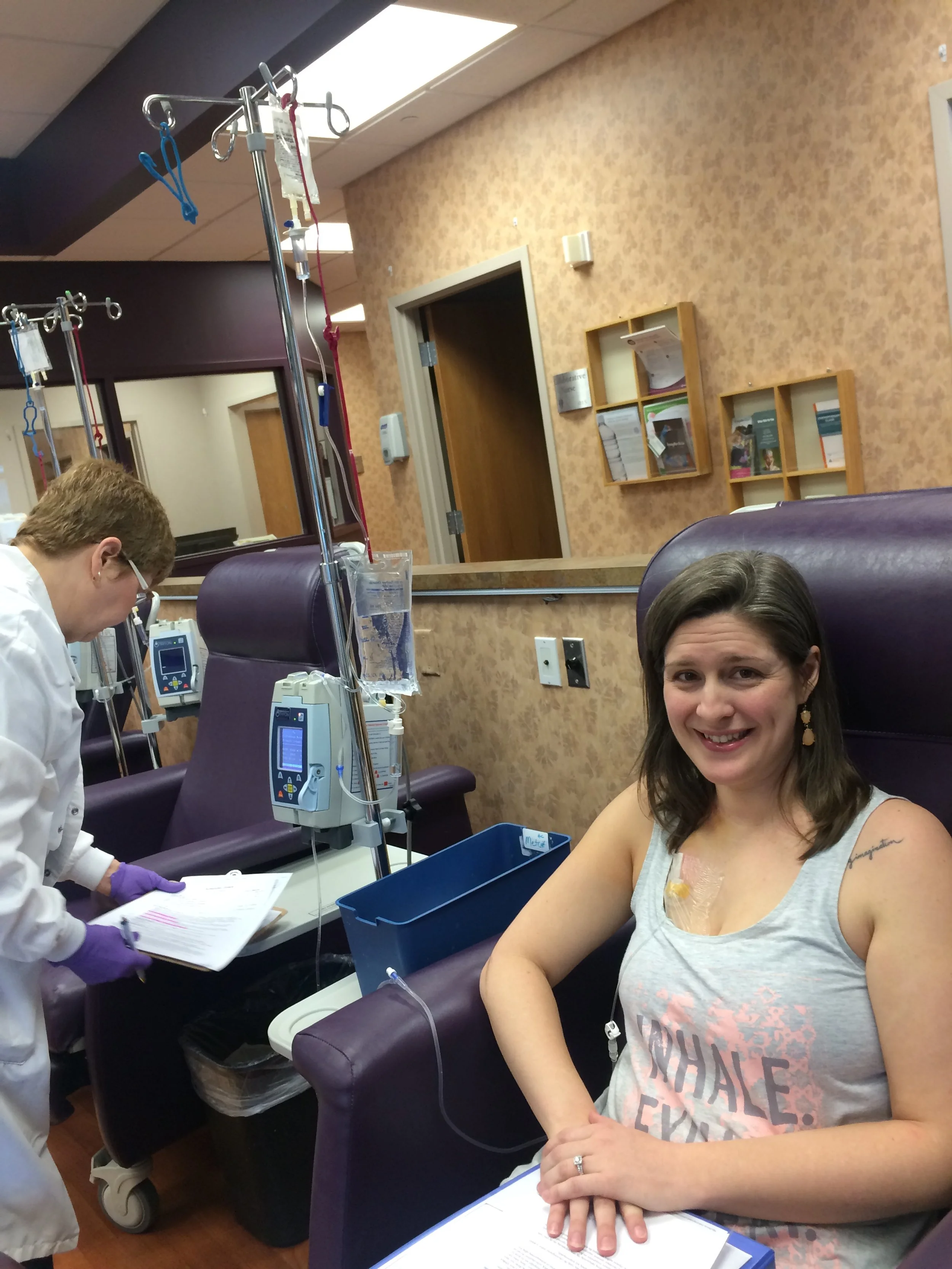

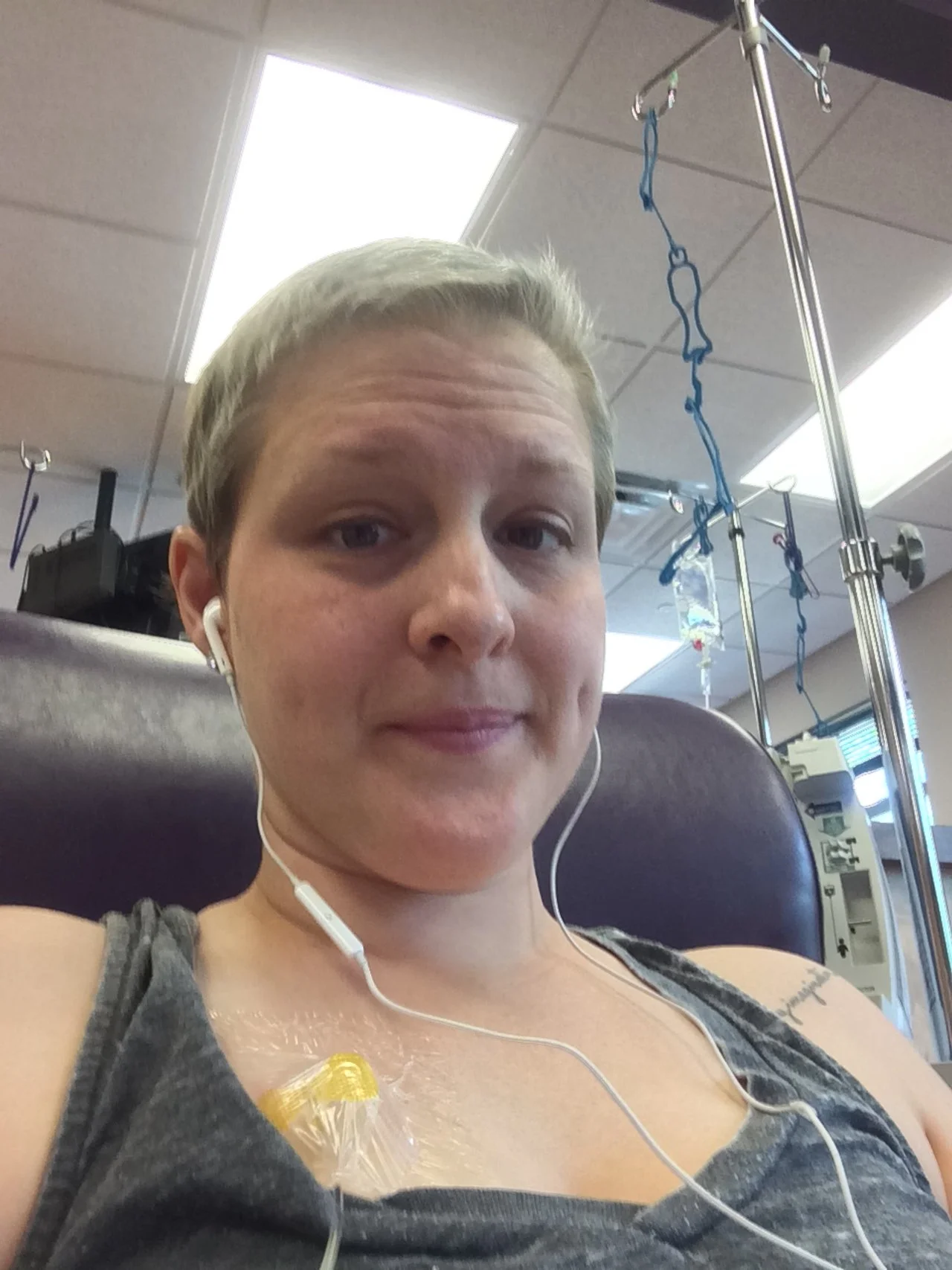

January 2026 marks 10 years for me since my cancer diagnosis. In January 2016, at the age of 34, I woke up one Saturday morning to find one of my breasts swollen, red, warm, and discolored. There had been no indication of anything wrong the night before. Within a week I was already receiving my first chemo treatment and had been diagnosed with Stage III Inflammatory Breast Cancer. I spent the next year in active treatment, and five years after that on hormone suppressants and bone-strengthening infusions.

My life changed overnight. Suddenly my professional worries about my career, my insecurities about being a new step-mom to young girls, and my plans and goals for the year were all overshadowed by learning a new vocabulary to talk to oncologists, managing a calendar of competing doctors appointments, and researching cancer resources online. My friends and community showed up – people fed my family three times a week for over six months, friends took the kids to soccer practices and movie nights, and cards, flowers, and gifts arrived regularly at the house reminding me that I was not alone.

But I felt alone. I felt arrogant, for assuming that I would live 80 or 90 years. I felt confused and angry and blindsided by the diagnosis. I felt annoyed by the way it was inconveniencing my life. I felt resentful of the women in my online cancer support groups who had embraced the identity of breast cancer survivor and all of the pink ribbon paraphernalia that went along with it. I didn’t want this new life or this new identity. I just wanted things to go back to the way they were.

But I also saw something else in those inflammatory breast cancer groups – no matter how they approached the issue, no matter how enthusiastic or cheerful they seemed, some of them were dying. One day they would be posting in online chats and suddenly they would be gone. Or unexpectedly one day we would get an update from their spouse or friends letting us know they had passed. Simultaneously, my chemo treatment wasn’t working well and we were reaching the limits of what the doctors could prescribe without permanently damaging my heart muscle. It became very real for me that I could die from this in my early 30s.

When it started to dawn on me that I might actually be dying, I wanted to talk about it, but it was hard to find folks willing to engage in that conversation. My very loving and supportive family and friends were still living their lives – jockeying for that promotion at work, trying to find their kids a ride to soccer practice, overinterpreting their mom’s latest text. They weren’t ready for conversations about death and dying, and – while I had always been terrible at small talk at parties – now I was trying to strike up conversations with strangers about mortality and death. I didn’t want to overburden my young step-kids with my fears and my spouse was going through his own journey trying to cope with my diagnosis. The folks at the cancer center understood somewhat, but I was also one of the youngest people there. If I tried to talk about the reality of dying, it felt like I either got dismissive reassurances not to worry because I was going to “beat this” or general pity about how unfair it all was because I was so young. I felt really unseen. I felt like I had become some faceless “cancer patient” who was disconnected from who I was and how I had lived my life.

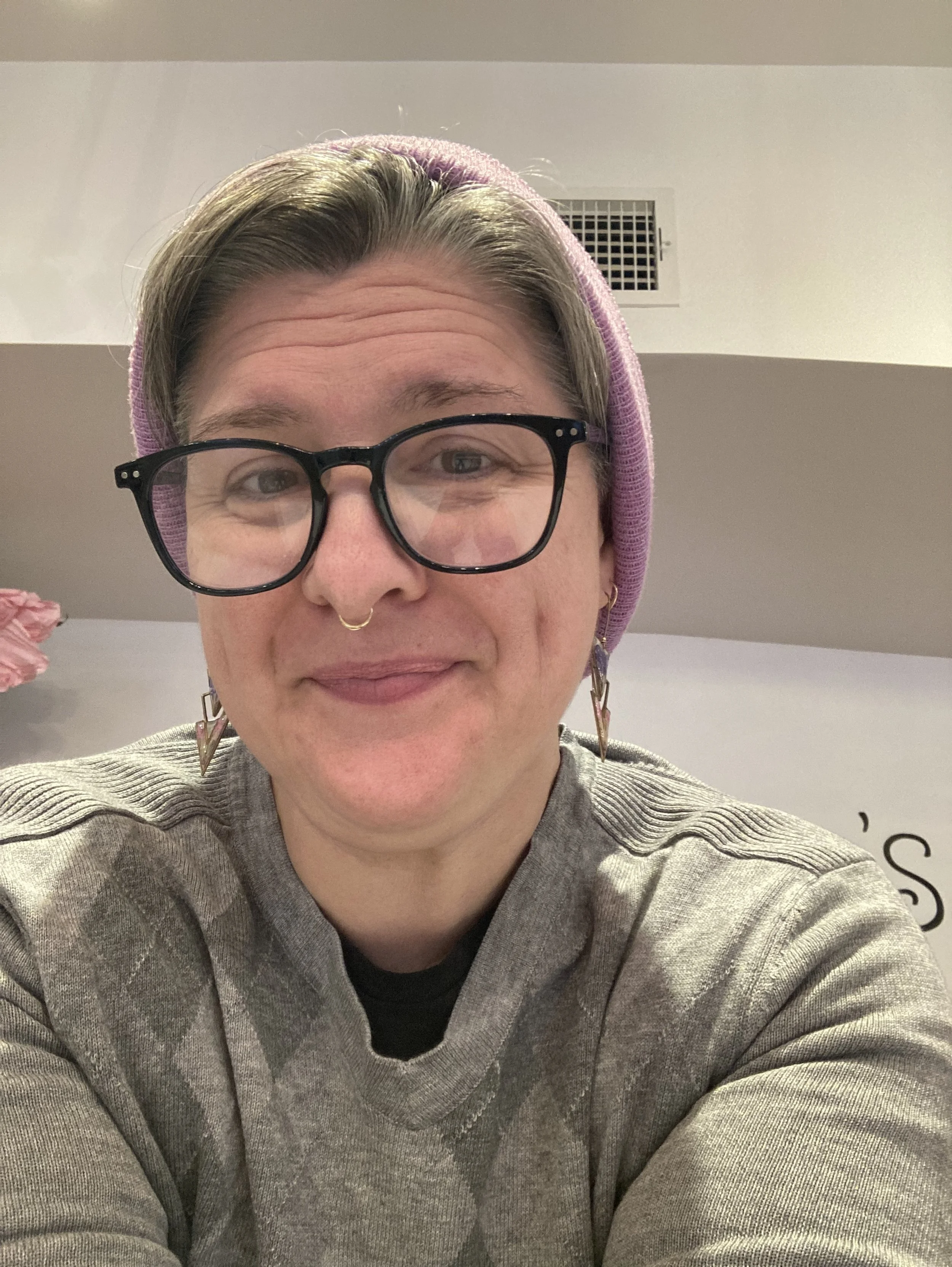

After eleven months of treatment and wondering about the prognosis – I didn’t die. Ten years later and in full remission, I can say that experience changed the way I approach my life. It sparked a curiosity for a better understanding of human mortality and what death can look like.

When I work with clients as a death doula, I am deeply interested in who they are as a person, beyond all the diagnoses and medical treatments. I am particularly passionate about working with young adults facing unexpected diagnoses – because it resonates so closely with my own lived experiences. Sometimes my presence allows clients to finally cry after a long week of “holding it together” for friends and family, sometimes my visits allow them to ask questions they’ve been afraid to ask anyone else, other times I’m just a safe space where they can vent frustrations about everything that has happened without feeling the need to edit or self-censor.

Ten years ago it felt unimaginable that I would be here doing this work and I am keenly aware that these are years I wasn’t sure I would have. I’m grateful to be able to use my experience in ways that can bring comfort and reassurance to clients and their loved ones. There is something deeply sacred and also fully human about facing death and I am grateful to be a small part of that story for people I serve.